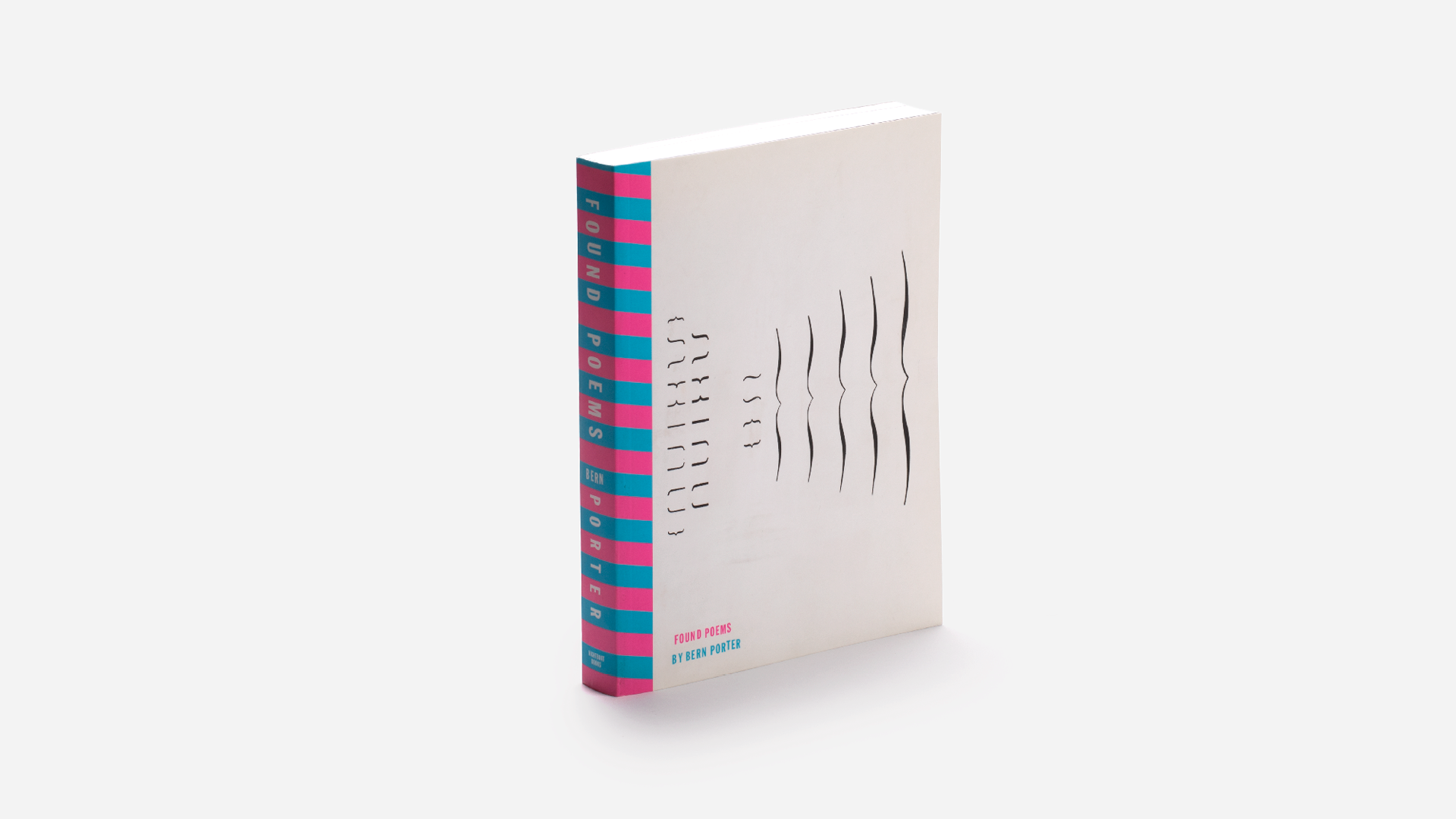

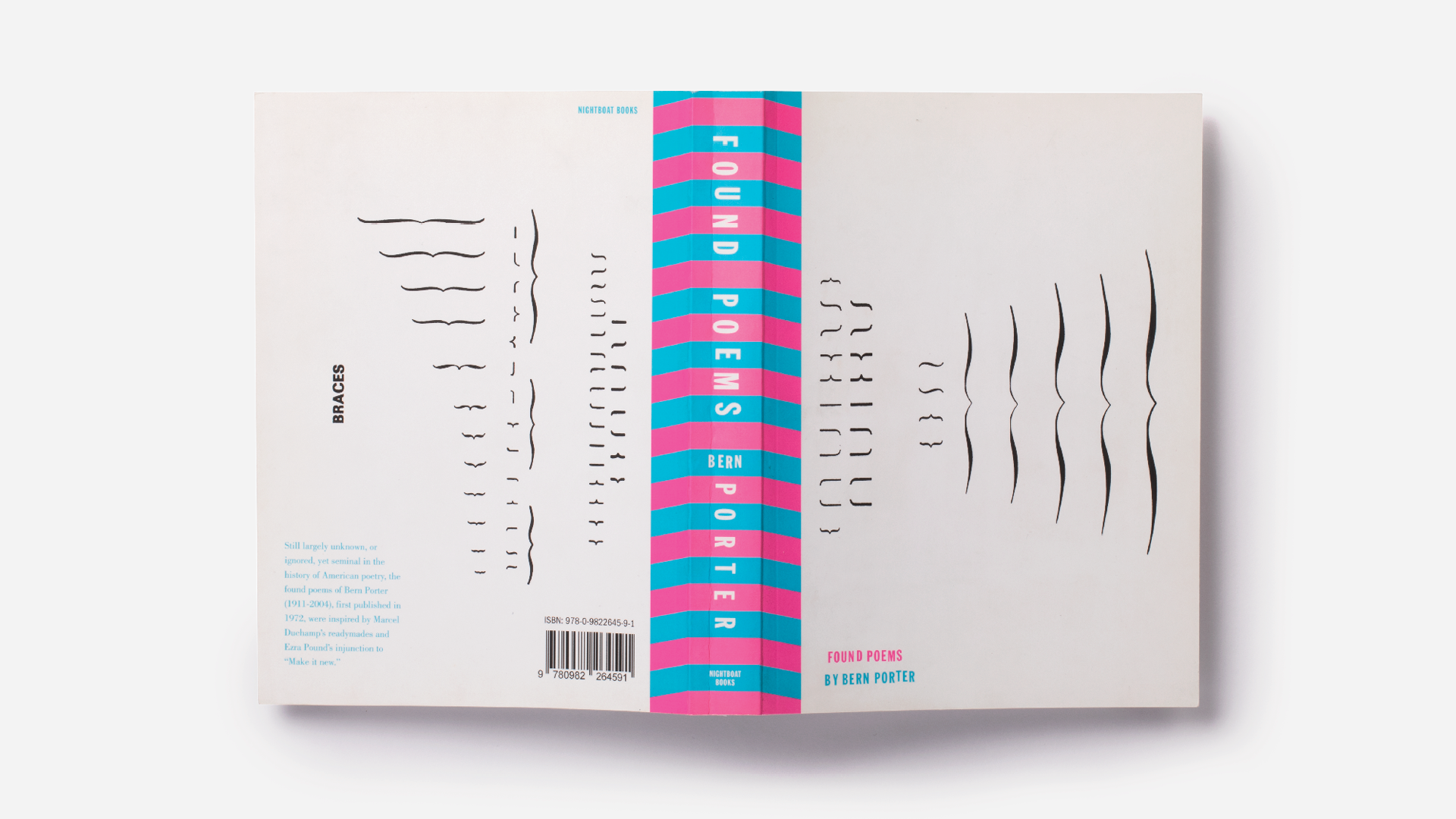

BERN PORTER

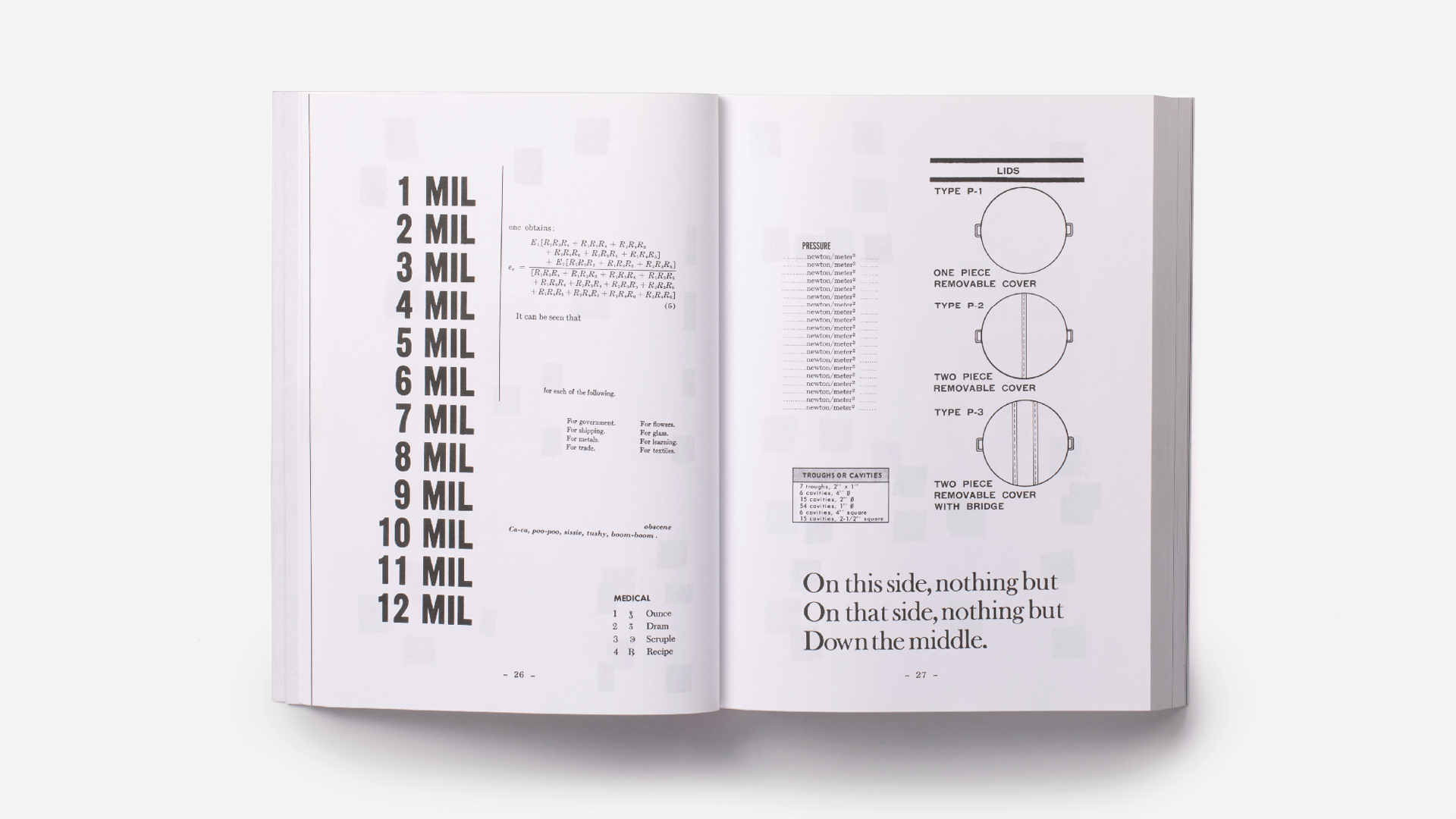

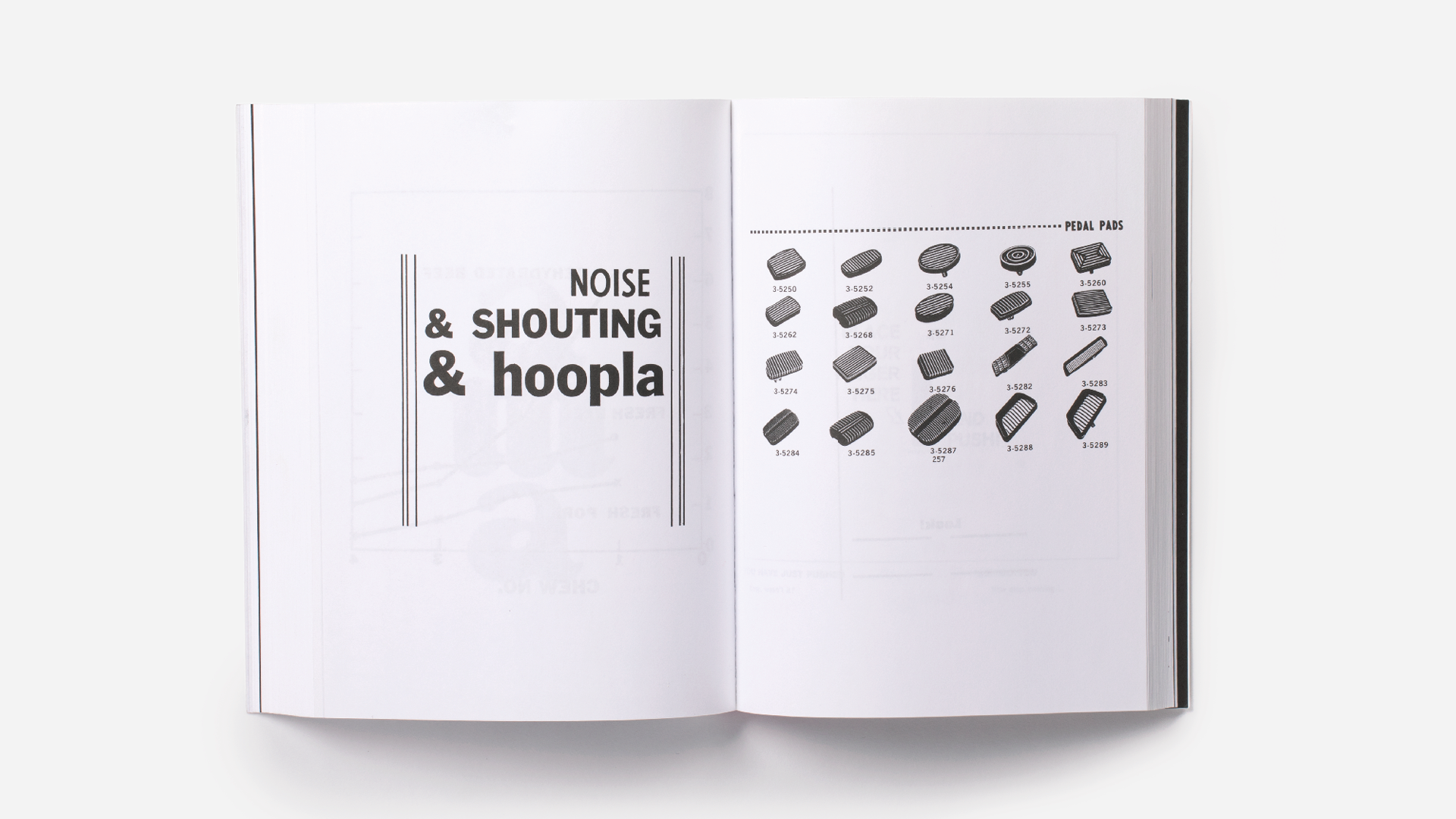

As a young designer I kept my copy of Found Poems close. Found Poems was my endless well of vernacular typography and design, a window into an evocative world of American hucksterism and mass marketing. Long out of print, I was eventually determined to get my favorite book back in circulation so I approached Nightboat Books, and working closely with them we re-packaged this classic text. As Dick Higgins said, “Porter’s Found Poems have the same seminal position as Duchamp’s objets trouvées.” This book collects Porter’s strongest “Founds,” his combinations of mass-media images and text that he used to reflect American culture, and includes an introduction by David Byrne.

About Bern Porter

Original edition of Found Poems (with Porter on the cover), published in 1972 by Something Else Press

On February 14, 1911, from a small farmhouse in northeastern Maine, was born a man, Bern Porter, who would after World War II stretch poetry’s traditions past the frontiers of authorship, context, voice, shape, and sound. Creator of over 100 books published by non-mainstream presses, including his own, and theorizer of “sciart,” the union of science and art, there was no other twentieth century poet like Bern Porter. In the late 1960s, after stormy and traumatic employ for twenty years as a Manhattan Project physicist, Saturn Moon Rocket engineer, and transcontinental communications specialist, Porter was exiled without due process from the National Security State. Choosing to exist on the edges and never giving up, Porter prodded humanity always to consider new approaches to its problems and dreams. A Correspondence Art pioneer, he was called during his lifetime “the da Vinci of the Atomic Age,” “the Charles Ives of American Letters,” and “the Poet Laureate of the Universe.” Today, Bern Porter’s massively creative motherlode serves as an inspiration to a new generation of artists and writers. Publishers Weekly concurs, writing, “There is no question that no one was doing quite what Porter was doing when he was doing it, and that lots of people are doing versions of it now.” Bern Porter died on June 7, 2004, in Belfast, Maine, where he had lived since 1972, as both a recluse and town gadfly, at his Institute of Advanced Thinking, a “school for drop-outs.” Its grounds were adorned with his found sculptures and poems, along with the world’s only horizontal orgone accumulator, on which, he claimed, many new lives were conceived.

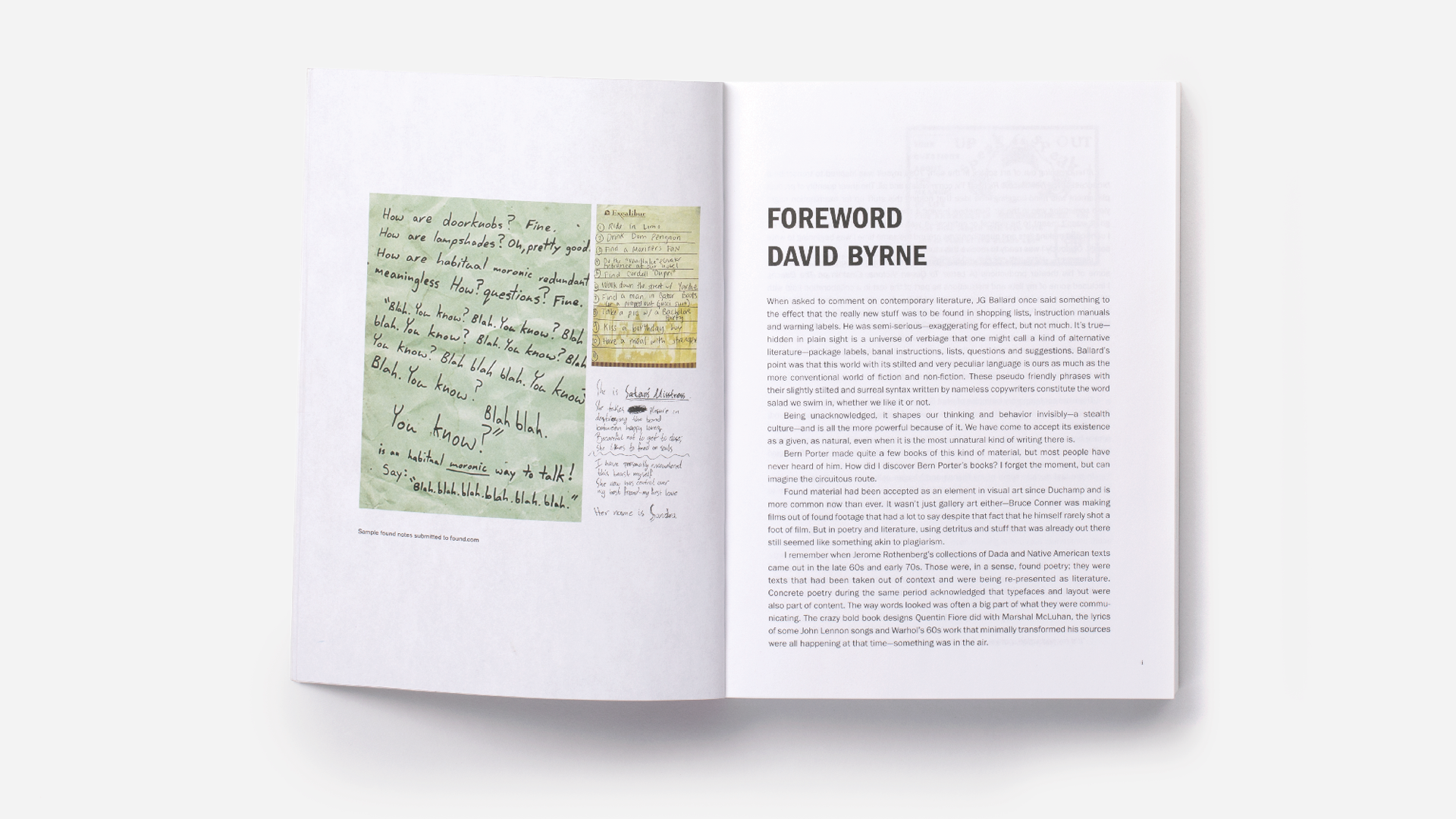

Excerpt from David Byrne’s introduction

When asked to comment on contemporary literature, JG Ballard once said something to the effect that the really new stuff was to be found in shopping lists, instruction manuals and warning labels. He was semi-serious—exaggerating for effect, but not much. It’s true—hidden in plain sight is a universe of verbiage that one might call a kind of alternative literature—package labels, banal instructions, lists, questions and suggestions. Ballard’s point was that this world with its stilted and very peculiar language is ours as much as the more conventional world of fiction and non-fiction. These pseudo friendly phrases with their slightly stilted and surreal syntax written by nameless copywriters constitute the word salad we swim in, whether we like it or not.

Being unacknowledged, it shapes our thinking and behavior invisibly—a stealth

culture—and is all the more powerful because of it. We have come to accept its existence as a given, as natural, even when it is the most unnatural kind of writing there is.

Bern Porter made quite a few books of this kind of material, but most people have never heard of him. How did I discover Bern Porter’s books? I forget the moment, but can imagine the circuitous route.

Found material had been accepted as an element in visual art since Duchamp and is more common now than ever. It wasn’t just gallery art either—Bruce Conner was making films out of found footage that had a lot to say despite that fact that he himself rarely shot a foot of film. But in poetry and literature, using detritus and stuff that was already out there still seemed like something akin to plagiarism.

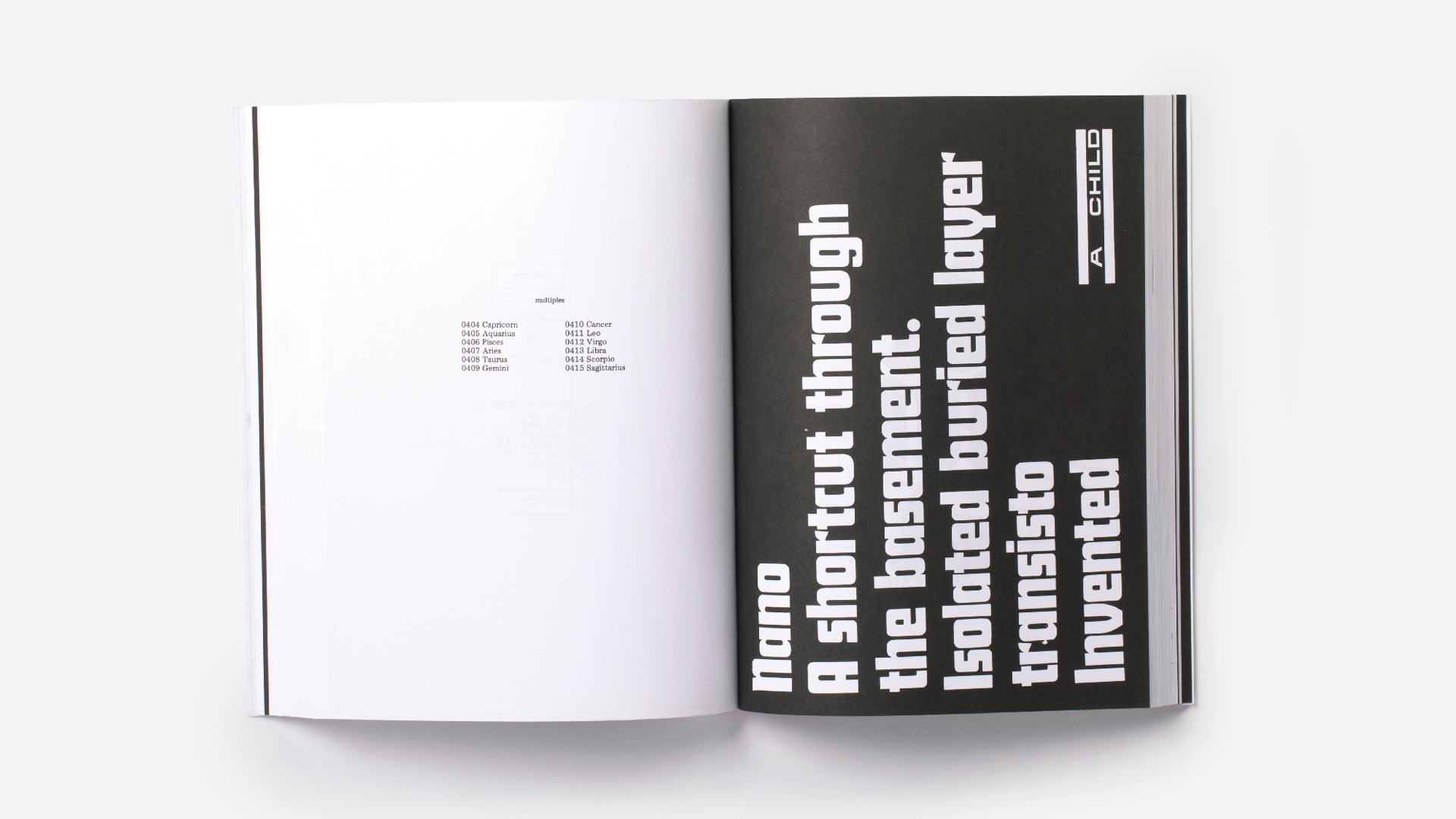

I remember when Jerome Rothenberg’s collections of Dada and Native American texts came out in the late 60s and early 70s. Those were, in a sense, found poetry; they were texts that had been taken out of context and were being re-presented as literature. Concrete poetry during the same period acknowledged that typefaces and layout were also part of content. The way words looked was often a big part of what they were communicating. The crazy bold book designs Quentin Fiore did with Marshal McLuhan, the lyrics of some John Lennon songs and Warhol’s 60s work that minimally transformed his sources were all happening at that time—something was in the air.

After dropping out of art school in the early 70s I myself was inspired to transcribe a broadcast of The New Price Is Right off TV, commercials and all. The sheer quantity of product placement was mind-boggling. The idea that holding this stuff up for examination might yield something was in the air. Somehow leaving it raw and unfiltered seemed the way to go. It wasn’t meant to be cynical or satirical—it was simply meant to say “this is here.”

I continued making lists and questionnaires around the same time I was beginning to write songs. Obviously I was ready to receive this stuff…

Title: Found Poems

Author: Bern Porter

Publisher: Nightboat Books

Date: 2011

Credits: Peter Buchanan-Smith (creative direction and design); Jeff Stark (design)